Investors instinctually get on and off the train at the wrong time

There is a common assumption that average market performance and average investor performance are roughly synonymous. If the market has a good five-year run, investors have a good run. If the market is down over five years, investors, on average, lose money. However, since the market almost always goes up in the long run, a patient and diversified investor should get solid long-term results, right? That is what most believe.

The problem is that investors, on average, do not succeed in taking advantage of long-term trends. They do not approach the market in an entirely rational, wholly prudent way. Great market news excites people and spurs them to buy when prices are high. Sharp drops and prolonged downturns discourage or frighten people into pulling back and liquidating assets.

I have seen this happen many times. Nearly every new client has made this mistake. They maximized their deposits into accounts during up times, and minimized their holdings just as values were set to start a cyclical run-up. My Aunt Sophie was a Depression-era woman who never bought stock because she could still remember people who lost everything in the 1930s. In August 1987, after five years of watching stocks rise steadily, she finally decided she was missing out on a good thing and wanted to jump into the market—right at one of its peaks. Fortunately, I delayed her decision long enough for her to avoid Black Monday, which came one month later.

On the other side of the ledger, I’ve seen people crushed emotionally in bear markets. They say, “I just can’t take it anymore!” and they liquidate everything—just in time to miss the next huge rebound. On reflection, it seems that every time the market peaks or hits bottom, I get a call from someone eager to buy or sell at the worst possible moment.

You can see this phenomenon on a macro scale. In 2000, the year the mega-bull market in equities finally ended, investors poured more than $200 billion in new money into stocks—the highest infusion of new cash ever. They were boarding a train that had already run out of steam. The market yo-yoed all that year and wound up down 3 percent. The next two years were much rougher. By the fall of 2002, the market was filled with undervalued stocks and poised for the four-year cyclical bull market (a rally within a secular bear market) that followed. But investors put less than $40 billion in new money into equities that year. They got off the train, just as it was ready for another very good run.

The Dalbar Study

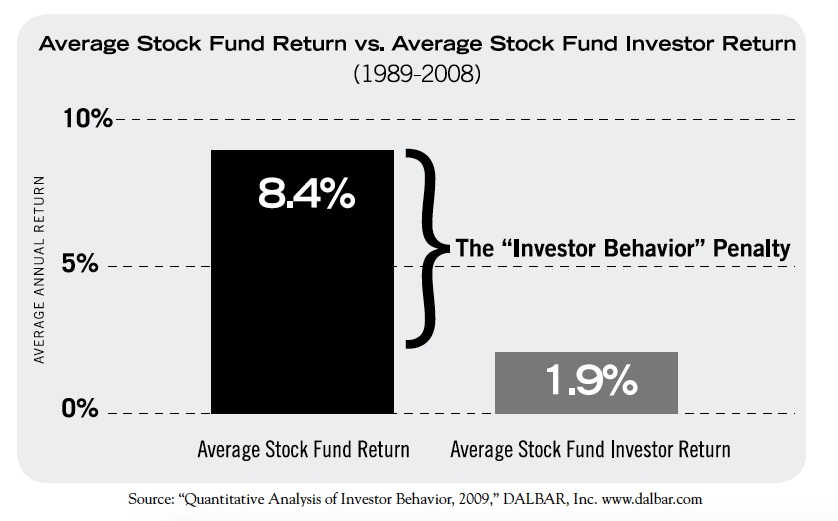

Investors do worse than average, according to a DALBAR study

You can see the long-term consequences of rear-view mirror investing in this study by Dalbar Inc., a leading financial services market research firm. The study looked at month-by-month data that showed when investors bought shares in mutual funds, sold those shares, or exchanged them for other shares over a 20-year period (1989 to 2008). All this data on investment decisions allowed them to simulate the behavior of an “average investor.” Here’s what they found:

- Over the 20 years studied, the S&P 500 had average returns of 8.4% annually.

- The inflation rate over this timeframe was 2.9% annually.

- The average mutual fund investor had returns of 1.9% annually.

That’s right. The average investor didn’t keep pace with inflation! Investors actually did fairly well in 14 of the 20 years studied, but the bad decisions they made in the other years significantly undermined their long-term performance. Dalbar stated its own conclusion succinctly: “When the going gets tough, investors panic.”

Joseph J. Janiczek is the founder and CEO of Janiczek Wealth Management. This article is adapted from his book, Investing from a Position of Strength.